- Home

- Herbie J. Pilato

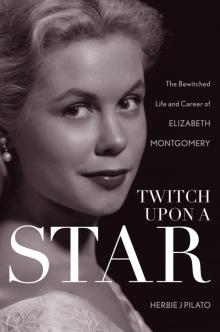

Twitch Upon a Star Page 3

Twitch Upon a Star Read online

Page 3

“Then you better get going.”

We said goodbye, I hung up, packed my guitar and was out the door.

By the time I reached Wilshire, Elizabeth had already called Billy to tell him I was on my way. When I arrived at his shop, he was standing at the counter. I shook his hand, explained about the guitar, and a few days later, it was like new again.

We chatted about his Mom, and I immediately noticed he had inherited her down-to-earth demeanor. When I told him so, he shared a few stories of what it was like growing up as not only her son, but the son of the legendary director Bill Asher.

He recalled a time in 1968, when he was just four years old, and a certain bewitching “screen transfer” proved somewhat confusing for him.

One Thursday night at around eight o’clock, he was at home watching his Mom on TV. It just so happened that Thursday night was the one day a week when the Bewitched cast and crew worked later than usual. Elizabeth did not usually arrive home until about 8:15 or 8:30 PM, but this one night she walked in the Asher’s front door, just as Samantha popped out on Bewitched. Eight-year-old Billy was startled. “Geez, Mommy,” he said, “… you really are a witch.”

Elizabeth offered a careful explanation: “No, Honey … I just play one on TV.”

Another time, when Billy was a teenager, circa 1977, he was again in the Asher living room but this time with a friend who was unaware of his heritage. At one point, Elizabeth walked in the room to get a magazine off the coffee table.

His friend screamed, “Oh, my gosh! It’s Elizabeth Montgomery!”

“Naw,” Billy said, ever carefree. “That’s just my mom.”

Not one to boast about position or social status, Billy, along with his brother Robert (named for Elizabeth’s father) and sister Rebecca (named for her grandmother Becca) always chose to walk with dignity and integrity, as they do to this day.

Rebecca has always been cordial in the few phone conversations we’ve shared, displaying her mother’s sense of humor each time. When I first talked with her, it took her a few weeks to call me back—just as it had been with Elizabeth. When I mentioned this to Rebecca, she laughed and said, “It must be genetic.”

Genes had everything to do with it, especially when it came to Elizabeth’s grandmother Becca, for whom her daughter was named—and whom she brought up at the close of our third interview in 1989—following my confession.

“You know who I really am, don’t you?” I posed, if somewhat cryptically.

“No,” she said, followed by a cautious pause, “… who?”

“I’m your guardian angel.”

Surprised and relieved, she smiled sweetly and said, “The last person who referred to themselves that way was my Grandmother Becca. And if it’s true—that you are indeed my guardian angel sent to replace her—well, then you better do one hell of a good job.”

More than twenty years after that exchange, I make an earnest attempt to do just that with this book, which could be described as part biography, part media history guide, part psychology book, part mystic primer, part political dossier, all trustingly compelling.

But Lizzie placed high expectations on biographies, in particular, referring here to the one-page actor profiles that publicists for the studios and networks put together to promote the TV show or film in which a given actor is currently starring:

I’ve always found them very self-conscious and they’ve always bothered me. I’ve never found one that somebody’s written that I’ve liked. I always think they are dry and stupid, and don’t really mean much to anybody.

Hopefully, Twitch Upon a Star: The Bewitched Life and Career of Elizabeth Montgomery, will mean something to someone—be it a member of Elizabeth’s family, a friend, a fan—because it’s a real story, a human story, an honest story—because sincerity was one of the many virtues which Elizabeth held dear. It’s a profile in humility and generosity because such traits shaped who she was, strived to be, and became, and who she remains in the hearts and minds of millions. It’s a portrait painted with reminiscences of her playful spirit, intelligent mind, and expansive resume; it’s the sum of her intricacies and complexities.

I agonized over whether or not to present particular passages in this book; some may be disturbing to read; they certainly proved challenging for me to report. I’d type in specific paragraphs and then delete them; I’d paste them back in and then cut them out again. Finally, I decided to buckle down and include them because it was time to address the elephants in the room. The previous books were fan letters about a fantasy TV show, written as though seen through rose-colored glasses. With this book, I had a job to do. This time, it’s not a fairytale, but a true love story, and all true love stories are earmarked with happy and sad elements. As a human being, I was forced to ponder those elements; as a journalist, I couldn’t ignore what I heard, some statements of which were glaring. In previous books, as Elizabeth’s “angel,” confident, friend, or fan, I regret ignoring those statements; had I found the courage to reveal them, this story may have had a different ending.

I also sensed that if I had not elected to write an honest biography about Elizabeth, eventually someone else might do so and not as delicately as I believe the material is presented within these pages.

In either case, it was clear to me that Elizabeth was multitalented, multi-faceted and multi-complex; reclusive and protective; generous to a fault but private. She was anything but easy to figure out, certainly more challenging to analyze than any of her performances, and she delivered diverse interpretations of a myriad of characters with what appeared to be total ease.

One of her more off-beat roles was that of private detective Sara Scott in the 1983 CBS TV-movie Missing Pieces, a mystery story that was adapted from Karl Alexander’s novel A Private Investigation. Similarly, this book detects and connects the missing pieces of a clandestine and extraordinary existence as it expounds on the amazing journey of a public figure who employed her widespread image for a better world. It’s for the multitudes who remain charmed by the contrasting work of an actress before, during, and after her superstar-making twitch as a witch named Samantha, a beloved character who retained a fiercely independent spirit amidst other unique roles that were brought to life by a majestic, courageous, and real-life heroine named Elizabeth Montgomery.

At its core, Twitch Upon a Star: The Bewitched Life and Career of Elizabeth Montgomery, is about a celebrated individual who, for the sake of clarity, simplicity, and intimacy, and in tribute to her unaffected demeanor, will from here on be mostly referred to as either “Elizabeth” or “Lizzie,” both which she so modestly and endearingly insisted on being known as at different times throughout her life and career.

PART I

Prewitched

“I just never had the desire to be a star.”

—Elizabeth Montgomery, Look Magazine, January 26, 1965

One

Once Upon a Time

“I like to grow naturally instead of being pruned into formality.”

—Elizabeth Montgomery, TV Radio Mirror Magazine, November 1969

Elizabeth Montgomery literally grew up on television, making her small screen debut on December 3, 1951 in “Top Secret,” an episode of her father’s heralded anthology series, Robert Montgomery Presents, which aired on NBC between 1950 and 1957. She’d appear in a total of twenty-eight episodes, but it was in “Secret” that she played none other than the apple of her father’s eye. Written by Thomas W. Phipps and directed by Norman Felton, this episode also featured Margaret Phillips (as Maria Dorne), James Van Dyk (Edmund Gerry), John D. Seymour (Dawson), and Patrick O’Neal (Brooks):

Foreign service agent Mr. Ward (Robert Montgomery) brings his daughter Susan (Lizzie) on a mission to a country on the brink of revolution with spies on all sides complicating the matter at hand.

The “Secret” title may have represented Elizabeth’s off-screen desire for privacy, while other Presents headings also proved significant, such as “Once Upon a

Time,” written by Theodore and Mathilda Ferro; airing May 31, 1954. This time, Elizabeth played a newlywed who contemplates how different life might have been had she married someone else.

In real life, Lizzie didn’t just contemplate that notion, she lived it … four times, with Fred Cammann, Gig Young, Bill Asher, and Robert Fox-worth.

Ten years after the “Time” episode of Presents aired, Bewitched debuted with the Sol Saks pilot, “I Darrin, Take This Witch, Samantha,” narrated by Jose Ferrer. The show opened with his first line, “Once upon a time …”

Whether represented on Robert Montgomery Presents or recited on Bewitched, it was a fairytale phrase that Lizzie adored and which ignited her interest in both projects, especially Bewitched. As she recalled in 1989, Bill Asher was in the room when she first read that term in the initial Samantha script.

“Okay, I love it!” she said.

“That’s it?” Bill wondered. “Once upon a time, and you love it?”

“Yeah!” she mused. “Anything that starts out that way can’t be all that bad.”

It was a spontaneous decision that intrinsically represented the essence of her carefree spirit which, in turn, contributed in no small measure to the show’s enormous success.

In fact, before Jose Ferrer got the job, she had asked her father if he would narrate the Bewitched pilot. In the interview she granted to Ronald Haven for the Jordan laserdisc, she referenced her dad’s decline to speak life into Bewitched, calling his response, “very strange”:

“No … I don’t think so.”

“Why not?”

“It’s your show.”

“Ah, ok. All right.”

Elizabeth was disappointed, and she later told him so. She would have enjoyed him kicking off Bewitched, her new series in 1964, just as he had given a jumpstart to her TV career when she made her small-screen debut on Robert Montgomery Presents in 1951.

For Lizzie, success was at times a burden, especially when it came to public revelations. For one, her age was a sensitive issue, cloaked in a chicane. But as author and genealogist James Pylant explains, “Celebrity genealogies are always hard to trace.” In 2004, Pylant authored The Bewitching Family Tree of Elizabeth Montgomery for genealogymagazine.com. “Biographical data abounds,” he said, “yet there’s no guarantee of accuracy.”

Elizabeth played into such wriggle room. Various studio and network press bios document her birth year as 1936 and 1938. In reality, it was 1933, as recorded in the State of California, California Birth Index, 1905–1995, published in Sacramento by the State of California Department of Public Health, Center for Health Statistics.

When she died in 1995, a few obituaries listed her age as fifty-seven, trimming five years off her birth date. Others offered conflicting details about her marital status: some said she was single at the time of her demise; some said she was survived by her fourth husband, Robert Foxworth.

But the “marital mystery,” as Pylant put it, was orchestrated by the self-protective Lizzie, who kept a step ahead of the press. She viewed her relationship with Foxworth as confidential. Even their marriage in 1993 was shrouded from the media. The event took place at the Los Angeles apartment of her manager Barry Krost and not a soul knew about it until after the fact.

Nevertheless, she appears on the Social Security Death Index as “Elizabeth Asher,” the surname of her third ex-husband, Bewitched producer/director William Asher. There, at least, her birth date is correct—April 15, 1933—although “Elizabeth A. Montgomery” is the name listed on her death certificate. The “A” is either for “Asher” or “Allen,” the maiden name of her mother, actress Elizabeth Allen.

According to A&E’s Biography, Elizabeth Montgomery: A Touch of Magic (which originally aired on February 15, 1999), Lizzie’s middle name was “Victoria,” a moniker sometimes linked with royalty, as is the name “Elizabeth” itself.

But that fits. From the mid-1970s until her demise in 1995, she was known as Queen of the TV-Movies. On Bewitched, Samantha was crowned Queen of the Witches (in the episode, “Long Live the Queen,” September 7, 1967); before that Aunt Clara’s (Marion Lorne) bumbling magic mishaps forced Sam’s introduction to Queen Victoria (Jane Connell in “Aunt Clara’s Queen Victoria Victory,” March 9, 1967).

Before Lizzie basked in the sparkle of stardom as Samantha, she was born in the shadow of Robert Montgomery’s fame. The story of who she was begins with him; the seeds of who she became were indelibly planted by this versatile actor and political idealist—a father who was just as complex as his daughter; a daughter who had a father complex.

Five years after his marriage to Broadway actress Elizabeth Allen on April 24, 1928, Lizzie was born into her privileged childhood, at the peak of his film popularity.

Talented, handsome, athletic, rich, and famous, Robert had the right social credentials, coupled with a solid intellect. Before his stable career on the small screen of the 1950s, he was a feature film legend of the 1930s and 1940s.

Although he was a Republican, and she a Democrat, Lizzie followed in his social advocacy. It was difficult for her to fathom and accept the scope of his notoriety before she ever began to question her own. She would later ponder the harvested influence over a legion of Bewitched buffs, because she had seen the role celebrity played in her father’s life. Once she glittered with fame, it was hard for her to embrace praise even from those whose lives she helped improve.

A political promoter rooted with a conservative outlook, her father held a stoic position in moderate contrast to her liberal stance; but both believed in the American dream (and the freedom that goes along with it).

In 1935, he was elected to the first of four terms as president of S.A.G., the Screen Actors Guild. It was here his political agenda began to take shape. In this capacity, he gained publicity in 1939 when he helped expose labor racketeering in the film industry. He went on to become a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy Reserve, an assistant naval attaché at the American Embassy in London, an attendant at a naval operations room in the White House, a commander over a PT boat in the Pacific, and an operations officer during the D-Day invasion of France. He was awarded the Bronze Star and later decorated as Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor.

In 1947, he headed the Hollywood Republican Committee to elect Thomas E. Dewey as President. That same year he testified as a friendly witness in the first round of the House Un-American Activities Committee, denouncing communist infiltration in Hollywood. Following President Eisenhower’s 1952 campaign, he was called on by the Principal Head of State to serve as a special staff consultant to television and public communications—the first individual to hold such a media post for the White House.

Robert came to Eisenhower’s attention because of his affiliation with Robert Montgomery Presents. During the 1960s he was engaged in a futile campaign against the practices of commercial TV, which he summarized in the book An Open Letter from a Television Viewer (J. H. Heineman, 1968). Also in the 1960s, the decade in which his daughter would begin to turn the world on with her twitch, Robert served as a communications consultant to John D. Rockefeller III and a director of R. H. Macy, the Milwaukee Telephone Company, and the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. From 1969 to 1970 he was president of Lincoln Center’s Repertory Theatre.

Steven J. Ross is the author of Hollywood Left And Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics (Oxford University Press, 2011). On April 22, 2012, Ross appeared on C-SPAN at the Los Angeles Festival of Books. When asked what role Robert Montgomery played in the Hollywood/political game, he replied:

Robert Montgomery actually had gone to prep school with George Murphy and the two of them were very close friends and Murphy … during the late ‘40s and ‘50s was a very prominent Republican activist. In fact, he was Louis B. Mayer’s [MGM executive] point man going around the country and when in 1952 Eisenhower wanted some help from Hollywood, or should I say the GOP got Eisenhower help, the two people who advised him on media strategy were Montgomery and Mu

rphy. And Eisenhower liked the two of them so much that he basically told his Madison Avenue firm that had been hired to do the TV, “You can keep writing the ads, but they’re going to show me how to appear on TV.” Afterwards, Eisenhower asked both men to come to Washington with him. Murphy kindly deferred and Montgomery still kept his career but he actually had an office in Washington to help Eisenhower for eight years with sort of media appearances and helping him stage his presence. Remember … this is a period when TV is just really emerging as a national phenomenon and politicians don’t really know how to deal with television. They were teaching them things like how to use makeup, what color glasses to use, how to face a camera … how to do sound bites … how to hold your body, camera angles … everything that a sophisticated actor would learn, they taught to Eisenhower.

As recorded in James Pylant’s expertly researched Bewitching article Robert Montgomery was born Henry Montgomery, Jr. on May 21, 1904 in Duchess County, New York.

Beacon is commonly given as his birthplace, though he was actually born in Fishkill Landing. (Beacon was formed from the adjoining towns of Fishkill Landing and Matteawan in 1913.) Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) promoted Robert Montgomery’s movie persona as a sophisticated, well-bred socialite by embellishing the elite family background of its handsome star. And while the actor was born in a large house on the banks of the Hudson River, and his father served as an executive of a rubber company, the 1920 Federal Census leaves a somewhat different impression. Fifty-two-year-old Henry Montgomery, the vice president of a rubber factory, and Mary W., age forty-seven, with sons Henry, Jr., age sixteen, and Donald, age fourteen (all New Yorkers by birth), boarded in a Beacon hotel kept by William Gordon. Henry, Sr., was a first generation American, his father being Irish and his mother was Scottish. Mary W.’s father was a Pennsylvanian, while her mother was from the West Indies. Twenty years earlier, the 1900 Federal Census shows the newly wedded Montgomerys (“years married: 0”) boarded in William Gordon’s hotel, then in Fishkill. Private secretary Henry Montgomery (Sr.), age 32 (born in May of 1868) and ‘Mai W.,’ age 24 (born in March of 1876) were among the hotel’s many boarders. Mrs. Montgomery’s birthplace is listed as New Jersey and her mother’s birthplace is Jamaica. Robert Montgomery’s mother is named in biographies of her son as Mary Weed Barnard, but her maiden name was actually Barney. At the time of the 1900 federal census, the Montgomerys had been married a little over six months, their marriage date being 14 December 1899. Mrs. Montgomery appears twice on the federal census in 1900, the second instance being as ‘May W. Barney,’ age twenty-five, born in March of 1875 in New Jersey. Her marital status was indicated as single, then written over to read married. She is named as a daughter of eighty-one-year-old Nathan Barney, who rented a Third Street home in Brooklyn, wife Mary A., age fifty-six (born in October 1843), sons George D., age thirty-four (born in October 1865 in Connecticut), Nathan C., age twenty-seven (born in June 1873 in New Jersey), and Walter S., age eighteen (born October 1882 in New Jersey). A twenty-three-year-old Irish servant also made her home with the family. Mr. Barney was born in Pennsylvania, and Mrs. Barney was born in ‘Jamaica, W. I.,’ a fact consistent with what May W. Montgomery supplied in 1900. According to Genealogy of the Barney Family in America, Mary Weed Barney was born on 30 March 1875 in Bayonne, Hudson County, New Jersey, to Nathan Barney, Jr. and his second wife, the former Mary A. Deverell. The Barney genealogy identifies the parents of Henry Montgomery, Sr., as Archibald Montgomery and the former Margaret Edminston of Brooklyn. Henry Montgomery, a one-year-old, is found in the household of Irish-born Archibald Montgomery—a prosperous shipping merchant—and Margaret (born in Scotland) on the rolls of the 1870 Federal Census in Brooklyn.

Twitch Upon a Star

Twitch Upon a Star